‘I tried to escape with drugs, pills and alcohol’: Björn Borg on his misery and mayhem after quitting tennis

The sporting superstar walked away from success and adulation at 26 – much to everyone’s bemusement. He opens up about his secret life and the depression, cocaine, overdoses and aggressive cancer that almost killed him

a person who doesn’t say very much,” Björn Borg says with a wry smile. Which may be the understatement of the century. Borg, the greatest tennis player of his day, has spent 42 years saying nothing since he announced his retirement at the age of 26.

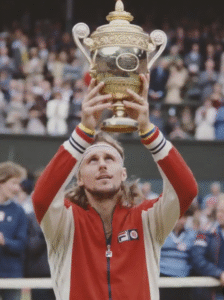

When he broke that news in 1983, it was one of the biggest shocks in the history of sport. Not simply because he was at his peak, but also because he was the rock star tennis player – beautiful, mysterious and followed by a flock of teenybopper fans. When Spain’s Carlos Alcaraz triumphed in the US Open earlier this month, aged 22, he became the second youngest player to have won six major tournaments. Borg beat him by four months.

Borg was actually only 25 when he stopped playing major tournaments in 1981. That season, he had appeared in three of the four grand slam finals, winning the French Open and losing at Wimbledon and the US Open. In total he won Wimbledon men’s singles five times in a row (a record matched only by Roger Federer) and six French opens.

And then he was gone, without a word. Borg devotees were traumatised. But perhaps they shouldn’t have been surprised at the lack of an explanation. The Swede was the samurai of tennis – immensely strong, disciplined and virtually silent. The “Ice Borg” never showed emotion on court, but many of us assumed there was a tumult roaring inside. And so it proved.

At the age of 69 he has finally written his memoir, Heartbeats, and it answers every question we’ve been asking for the best part of half a century. It contains revelation after revelation, and is all the more shocking for the understated style in which it is written. Drugs, alcohol, despair, near-fatal overdoses, failed relationships, shame and self-imposed exile: for any Borg fan – and I was a huge one, growing up – it’s a painful read.

We’re talking via video link. He’s in Stockholm at his publisher’s offices. His hair is now grey, but still luxuriant. He looks super-fit, partly because of an exercise regime so batty that only Borg could come up with it. From the off, he tells me how much he disliked talking in the old days. This accounts for the fact that so few TV interviews exist of him (you won’t have to look hard to find footage of rivals such as Jimmy Connors or John McEnroe, or, from the women’s game, Martina Navratilova and Billie Jean King). Borg tried his hand at commentary, but that proved a short-lived career when he just sat there in silence.

“I’m a very secret person,” he says. “And I’m a very stubborn person.” That stubbornness, or discipline, was at the heart of his success – never giving up, never giving in to emotion, never giving into temptation. It was also at the heart of his failings – refusing to mix with his old tennis friends after he quit, refusing to use the new turbocharged rackets when he briefly returned in 1991 (which meant he had zero chance of winning) and refusing to explain why he retired in the first place.

So why has he decided to tell his story now? “It’s been bothering me for many years. People know me as a tennis player, but not what I went through. The decisions I took in my life were stupid, so I wanted to tell that story.” It’s so Borg-like that he feels the need to own his stupidity rather than his success. But, he says, he knew he couldn’t tell his story to a stranger, and he didn’t feel capable of telling it himself.

A few years ago he asked his third wife, Patricia Östfeld, whom he has been with for 23 years, if she would help him write the book. “I was very happy she said yes because if she hadn’t this book would never have come out. I would have taken my story to the grave. She said, ‘What d’you want to put in it?’ and I said, ‘Everything. I want to be open.’”

Borg adored tennis in the early days – not just the success, but the game itself. But by 25 he was burnt out. “Up to that point I was entirely focused on my tennis. I was eating, sleeping, practising, playing matches. And I loved it. I had a great time.” So what happened? “I lost my motivation.”